Years ago, a friend who’d served with me in Peace Corps Ukraine asked if I knew of any graphic novels based on civil rights history. A social studies teacher at International Community High School of the Bronx, he wanted attractive materials to facilitate student interest. At the time, I wasn’t very helpful, but today I could suggest several titles, premier among them March by John Lewis, Andrew Aydin, and Nate Powell. I’d add Sybille Titeux de la Croix, Amazing Ameziane, and Jenna Allen’s Ms. Davis: A Graphic Biography. And finally, there’s The Black Panther Party: A Graphic Novel History by David F. Walker and Marcus Kwame Anderson. I know I’m missing others.

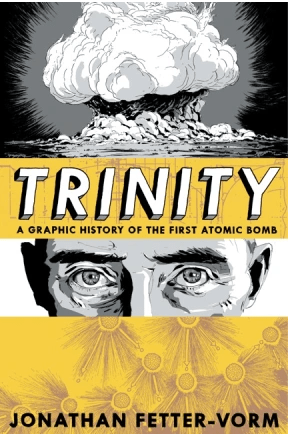

Overall, twentieth-century history has become quite an inspiration for graphic-novel creators. I’ve experienced Derf Backderf’s Kent State: Four Dead in Ohio and The Age of Selfishness: Ayn Rand, Morality, and the Financial Crisis. Many rightfully have praised Art Spiegelman for his Maus series, as well as Marjane Satrapi for Persepolis. Whether purely from a historical perspective or through personal lenses, authors and artists are filling bookshelves with graphic accounts of feminism, immigration, LGBTQIA+ issues, and anything else of interest to anyone — adult or child — looking for introductions to any number of topics. To this list, I’ll add Jonathan Fetter-Vorm’s Trinity: A Graphic History of the First Atomic Bomb.

I was born in 1965, on the cusp of baby boomers and Generation X, and nothing provoked more generalized anxiety during our formative years than the bomb, that reality heaped upon us by J. Robert Oppenheimer and his colleagues at the Manhattan Project, those Destroyers of Worlds. When would it come? Sting famously hoped that the Russians loved their children too, for Hell’s sake. Even after the fall of the USSR, societies still had cause for worry. What if rogue elements like North Korea or Al Qaeda were to score nuclear capabilities? North Korea’s crossed that finish line, of course, and we know it – oh, how we know it. Mother, will they drop the bomb on us? Some are still looking over their shoulders and up at the sky.

Fetter-Vorm centers his narrative around July 16, 1945, the day the first atomic bomb was detonated in the Jornada del Muerto desert, New Mexico. A part of the Manhattan Project and codenamed Trinity, this bomb equaled 25 kilotons of TNT. Oppenheimer himself chose the codename Trinity based on lines from John Donne’s sonnet, “Hymn to God, my God, in My Sickness.” He’d been introduced to Donne by his former fiancée, Jean Tatlock – a psychiatrist and member of the Communist Party — who killed herself in 1944. I must believe that Oppenheimer fully knew what irony he was provoking by naming a massive bomb test after a poem that opens with “Batter my heart, three person’d God.” The brilliant physicist also was well read not only in dead white men but in Sanskrit poetry as well, and so hence his famous “Destroyer of World” reference from the Bhagavad Gita.

Readers won’t get much beyond the Trinity event from Fetter-Vorm, however. He’s working only with just over 150 pages, so he’s laser-focused on discussing scientific discoveries that led to Trinity and the politics surrounding later decisions to employ this technology on Hiroshima and Nagasaki. To experience wonderfully complete detail overloads, obtain Richard Rhodes’s The Making of the Atomic Bomb and American Prometheus: The Triumph and Tragedy of J. Robert Oppenheimer by Kai Bird and Martin J. Sherwin. The latter is the basis for the film Oppenheimer (2023).

This is the place to start, however, the place to give intermediate and young-adult readers a taste of nuclear science and the history surrounding it. For once, I understand the differences between gun-type and implosion bombs. A few of Fetter-Vorm’s images are stark, pulling no punches about the immediate effects Little Boy and Fat Man had on Hiroshima and Nagasaki, and the dreadful radiation poisoning that lingered all too long.

Critiques have included the author/artist’s apparent propagandizing of elements surrounding the decision to bomb sites in Japan, questioning whether he distorts Japan’s attitudes toward surrender. I see the point here. Kai Bird and Martin J. Sherwin offer more balanced perspectives on this matter. Overall, however, with Trinity Fetter-Vorm blends science, history, and politics to illustrate that so terrible day out in the New Mexican backcountry. All we are saying is give peace a chance.