The Beginning

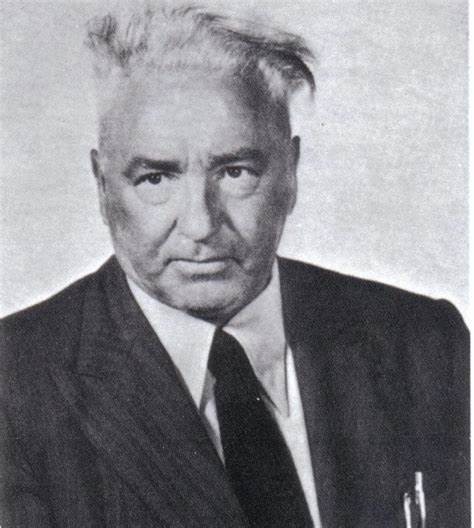

I spent over a year deciding how best to approach Mark Antonucci’s death. When I met him, Mark was the clinical director of Suicide and Crisis Services (SACS), now the Crisis and Suicide Prevention Lifeline-988 (CSPL-988). More than anyone else, Mark was responsible for how I approach what remains my vocation nearly 37 years after our first encounter. More about that later. It’s worth the wait.

A mutual friend, Jack, told me Mark was retiring from the County of Santa Clara after several decades. Mark and I hadn’t talked for two or three years, so I didn’t know that he was experiencing memory loss. Mark had left SACS 20 years prior, taking a position with the Behavioral Health Division’s Employment Assistance Program (EAP), where he was performing Short-term therapy for qualified county wage earners. Mark often praised my memory for details. Names and events haunt the hallways of my mind, indicative of the hyper-vigilance I developed as a bullied child. Hearing that Mark was stepping away from his career and regular poker games due to this deterioration left me cold.

Soon, he required inpatient care. Eventually, he didn’t survive COVID. His wife, Marlow, contacted me soon after. She was asking people to write something – memories, favorite anecdotes – anything shareable with others. Specifically, she wanted me to break down what training was like with Mark — not a writing task on par with neural surgery, but a complex one, given how much internal sorting I required before completing it.

Well, here I go.

During the fall semester of 1987, I was taking Social Psychology at San Jose State University. The professor, Ellen Kaschak, divided students into groups that met weekly. We paid attention to the developments among us and applied the concepts we studied in short weekly papers. A groupmate, Rita, was a volunteer with SACS and spoke copiously about her experiences, her training, and what she had to say about helping suicidal callers. When I expressed interest, she warned me that SACS kept strict acceptance standards, so I shouldn’t feel disappointed if I wasn’t invited to participate. Then she described “Dr. Mark” as “the most perceptive, warmest man.” The following week, I called and began the process.

The Phone Interview

Most applicants who weren’t ready to practice suicide prevention were weeded out at this level. Reasons entailed unresolved traumas or suicide grief, fresh suicide attempts, or perhaps the interviewer merely “sensed something.” Interviewers openly discussed concerns with applicants, suggesting they try again in a year when evaluators would assess their progress with targeted issues. Others received suggestions for other organizations seeking volunteers.

Phone interviews consisted of questions about interests and background, followed by a short role-play. Then, the interviewer explained that training included a clinical interview, observations with experienced volunteers, a screening, six classroom sessions, and a final weekend-long event, during which potential volunteers underwent intensive role-plays and feedback. At any step, potential volunteers not meeting standards were “asked not to continue.” I was scheduled for a one-on-one interview with “Dr. Mark.” My interviewer — Jean, the office manager, volunteer coordinator, and a trainer — wondered if I was too inexperienced. I was, but that didn’t stop me.

The Clinical Interview

“This motherfucker never blinks,” I thought while Mark probed my family history, possible trauma, how I processed loss, and any experience with suicide – losses or attempts. Intensely, he stared while writing notes, never looking down at his form. I assumed I was interviewing for a job, but Mark was performing a therapy intake. I recalled Rita’s description of him, especially the words “perceptive” and “warm.” Perceptive? Like functioning X-ray specs. Warm? Like Siberia in mid-December. I attempted to charm and gave answers I thought he wanted, but no. I was failing hard. He noted the deep red scar running across my forehead. I’d earned it from a recent auto accident.

Next, Jean delivered a role-play about a woman losing her vision. I lectured her about Braille. I explained how much blind people were learning these days. A different lifestyle? She’d adapt! Not once did I check for suicide. Not once did I allow space for emotional expression. Peppy me! Thankfully, they stopped me before I whipped out my top hat and cane or started waving jazz hands. After giving helpful feedback, Jean left the office, and Mark sighed. “Perhaps this isn’t for you. Are you sure you know why you’re here?” I thought I did. I might have walked out, but replied, “I want to do this.” He nodded. “You’ve got unresolved anger and, wow, not much life experience,” he added. “Watch out for that.”

Potential volunteers usually complete four mandatory observations with experienced volunteers before moving on to screening. Mark strongly suggested I do more. I did 12 over the month between this interview and my screening. Rita also practiced with me, telling Mark I needed tutoring, but I possessed the “stuff.” Mark responded that I must show clear improvement in my screening. The heat was on.

The Screening

Through observations and conversations with volunteers, I learned core values established by Mark, who avoided psychological jargon because many associated with SACS weren’t bound for mental health professions. These value terms permeated the feedback that potential volunteers absorbed after role-plays. If you’re thinking “wax-on/wax-off,” you’re correct. Sweat and repetition were key to opening our instincts, and I frequently heard the following:

- Fix-It: Rather than listening, a counselor might jump immediately to solutions. I did this throughout my clinical interview when Jean portrayed a woman losing her vision. Unsolicited advice is useless. The core values here are nonjudgmental listening, building honest connections with callers, and avoiding our self-motivated agendas. No one cares how much a counselor might know about bipolar disorder but how much a counselor will shut up and learn what that’s like from the individual’s perspective. Fixing it interrupts the expression of emotions, which we facilitate through active listening and open-ended, nonjudgmental questions.

- Avoid Yes/No Questions: As much as possible, we ask open-ended questions requiring more than a yes or no answer. This seems cliched, yet it reflects the core values of caller-centered crisis intervention, caller empowerment, and least-invasive methodologies. When callers feel that counselors have heard them, they feel validated and empowered, and if they’ve released those emotions, they will more clearly see what next steps best fits them. Effective counselors reflect and negotiate. They don’t dictate.

- Tracking: Are counselors listening intently enough to discern cues from their callers? If someone is describing a relationship issue, why suddenly ask about employment status? Again, active listening and caller-centered intervention are the goals.

- Poor Babies: These are honest verbal reactions to what callers are relating. They can’t see body language or expressions over telephone lines, of course, so telephone counselors train themselves to utter “wow,” “my word,” “good grief,” or whatever comes naturally to both indicate listening and to spur further emotional expression.

- Dig Deeper: Encourage details and emotional venting always. Don’t shy away from intense sadness or anger. Edwin Shneidman, the father of suicidology, speaks about psychache and unmet psychological needs being paramount among suicidal people, who must express their pain before moving past ideation. More about Shneidman later.

- Suicide Checks: Are you feeling suicidal? How are you thinking of doing it? Where are you thinking of doing it? When? The more specific answers callers supply, the more they’ve planned and the higher their risk. We were drilled on hitting cues with this right when callers gave them and, if necessary, to ask again. Like voting, do it early and often.

For the screening, three potential volunteers sat on a couch: Patty, Mary Tabor, and I. Several senior volunteers, referred to as consultants, surrounded us. They guided and supported both potential and new volunteers. Mark led the proceedings. Taking turns, each potential volunteer entered a small room with a telephone. We answered it when it rang and engaged with whatever role-play was presented. Twenty minutes later, the role-player stated, “We’re ending the call now,” and we returned to the larger room for feedback — three separate calls, along with feedback, made for a very long evening.

Toward the end, Mark sent the trainees out while he and the consultants reviewed whether they would see us at the six-week classroom sessions and, more importantly, the weekend training. Patty and Mary Tabor performed well, but I doubted myself. The three of us exchanged notes, laughed through our nervousness, and wondered what was being said about us. Finally, we returned to the couch that had, by then, become our haven. “We’d like you all to continue,” said Mark. He then outlined what he expected from each of us.

“I see your effort,” he told me. “I’ve never witnessed anyone evolve so quickly.”

“Miles to go before I sleep, I replied.

“What’s motivating you?”

“I want to do this job, but not altruistically 100%. What I’m learning about myself is painful, but I suspect — I hope? — it’ll be worth it in the long run. I am inexperienced at life, but I see how this will help when experience does smack me across the chops.”

Mark smiled, and I understood his previous distance was self-protection. He didn’t think I’d make it this far. I hadn’t crapped the bed, but miles to go, nonetheless.

The Classroom Sessions

Six lectures covering one or two subjects per evening comprised this unit, covering suicide-risk demographics, rape intervention, childhood sexual trauma, grief counseling, HIV+/AIDS, LGBTQIA+, mental illnesses, multiculturalism, general office procedures, difficult/repeat callers, and emergency dispatch. Mark didn’t choose these topics; the American Association of Suicidology (AAS), the national agency accrediting suicide prevention centers, mandated them for all training. However, he put his unique spin on them, feeding us data while consistently reminding us that facts about groups don’t always define individuals. Without the experiential role-plays, the main thrust of his training philosophy would have been useless. Nomothetic findings help clarify areas for exploration, but never forget how each person differs from others in any given set. By doing so, we miss opportunities to allow persons to educate us on their specific predicaments, thus empowering them and signaling that they’re being heard. I still hear Mark: “Get out of your head, Chuck.”

Anyone interested can learn about at-risk factors and find statistics on the AAS website: www.suicidology.org. The AAS also provides webinars, reading lists, and valuable public resources. I renew my membership annually and subscribe to Suicide and Life-Threatening Behavior, the AAS quarterly journal.

The Weekend Training

My struggle coalesced during the weekend training, when potential volunteers underwent two long role-plays each day, four total. I was one of twelve in the Class of June 1988, divided into sub-groups of three that traveled between breakout rooms, each filled with experienced volunteers giving and critiquing our role-plays. Mark determined which role-plays trainees faced and swore his choices were random. Bullshit. He interviewed us, screened us, and knew our soft spots like a film buff, quoting The Godfather line by line. Cruel? Not nearly. Would we crumble when callers confronted us with our vulnerabilities? Did we possess blind spots, or were we unfairly judgmental? For example, I drew the “gay relationship breakup” call, which is appropriate given that I’m a white, cisgender, heterosexual male. Additionally, Mark evaluated how we digested strong emotions and navigated our idiosyncratic crises. Essentially, he was putting us through crisis to teach crisis intervention.

Mark was the Leonard Bernstein of orchestrating groups. The anger symbolized by my facial scar surfaced hard in one breakout. Mark noticed that unresolved anger at my clinical interview. Others wept. One woman held me. These weekends were cathartic and replete with hippie leitmotifs. Participants sat in a big circle on pillows ringing the room. Mark led guided meditations, and much talk surrounded “getting in touch with your feelings.” Our center performed effectively because Mark blended many crucial ingredients for a healthy social body. The goals were bonding a community dedicated to public outreach and teaching how to turn the porch light on for tortured callers and our fellow counselors. Achievement unlocked.

Years later, an unfriendly entity opined that Mark led a personality cult. His methods might have overlapped with cult indoctrination, but the intention and result were authentically nurturing and buttressed self-expression rather than strict adherence. If anything, my active listening elevated from thought exercises to instinct. I was not trapped in my head anymore. I paid no money, and no one tried coercing me to conform mindlessly.

Sunday evening, the event closed as consultants met with Mark to discuss potential volunteers and if they were ready for phone work. The tone often got heated, and debates ensued, but very few didn’t pass at this point. Mark assigned consultants to monitor new volunteers’ first four shifts and then to guide them once they were fully vetted. I passed. My consultant was Jim Marshall, a no-nonsense type who ran a video rental shop in Boulder Creek. No contretemps arose, and four shifts later, I earned my independence. It’s not bad for a guy who almost got shown the curb months earlier.

I cleared 1,500 hours of volunteering before signing a dependent contract to staff overnight shifts full-time. Now nearing 60, I’m a coded county employee, the overnight lead, and a trainer. Younger colleagues have dubbed me the “Master Vampire,” not only a jab at my nocturnal lifestyle but an acknowledgment of my prowess, they tell me, because Anne Rice’s masters are powerful beings. I look toward Mark Antonucci, who taught me everything from counseling to understanding myself. I’m but a shadow, a remnant of his talents. Two or three generations of clinicians all over California have benefited from his supervision—quite a legacy, and if you include me, all credit to him, that life-changing bastard. You saved my life, Mark, more than once. May Odin himself serve your first cup of mead in Valhalla.

A Few Influences

SACS had a small library, but titles disappeared as volunteers never returned them, and eventually, management stopped replacing them or ordering new ones altogether. Mark rarely suggested books. I’d ask, of course, but he consistently demurred, maintaining his “learning best by doing” and “stay out of your head” stances. I, however, am not built that way, so to put me off, he revealed a few authors and ideas that influenced what and how he taught.

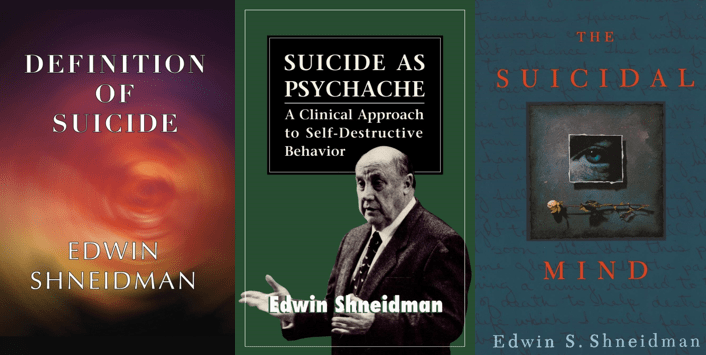

Edwin Shneidman

In 1949, Edwin Shneidman was working for the Veteran’s Administration in Los Angeles, where his supervisor instructed him to write letters to two widows whose husbands had committed suicide. Upon examining their files, Shneidman discovered that one had written a suicide note. His curiosity sparked, and over just a few weeks, he gathered 700 letters, beginning his life’s calling.

Today, we revere Shneidman for coining the term “suicidology ” and forming the AAS. He also inspired expansive suicide-prevention research with his colleagues Norman Farberow, Robert Litman, and Mickey Hellig. His theories have massively influenced my style.

Shneidman felt suicide stems from psychological pain, what he calls “psychache.” Thwarted or distorted psychological needs elevate suicide risk. Suicide and mental illness overlap because mental illnesses cause perturbation, frustration, unease, upset, and pain, but self-lethality does not necessarily mean mental illness. Psychache is a very subjective, persistent mental pain. As a psychologist and Professor of Thanatology at UCLA, Shneidman instructed that those wishing to help must reduce suicide by alleviating pain. Trust me, this is easier said than done, but his broad-minded approach strengthens flexibility when assessing personal attachments and how losses, or the threat of loss, enhance danger.

Parent Effectiveness Training (PET)

Thomas Gordon created PET to help parents avoid permissiveness by listening so children learn how to own and solve their difficulties. In return, children converse with their parents, relating needs and feelings and resolving conflicts through what Gordon terms the “No-Lose” method. All the hallmarks of good listening are present, for example, open-ended questions, nonjudgmental attitudes (if possible, with children who need boundaries), and reflective commenting.

I fully understand why Mark suggested Gordon. His framework emphasizes empowerment, and this fits nicely with SAC’s policies regarding least-invasive practices, meaning effective crisis counselors don’t impose solutions or immediately dispatch emergency responders. We listen, ask questions not from a script but genuinely in response to what callers tell us, and negotiate, not dictate. We encourage the open expression of emotions to build bonds and eliminate blocks that keep individuals from remedying problems on their own. At our best, we are facilitative street cleaners sweeping away rubble, barring people from reaching their destinations and saving their own lives with tools of their choosing.

Wilhelm Reich

Shockingly, Mark told me his doctoral dissertation involved Wilhelm Reich. At the time, all I knew about Reich was his concept for releasing orgone, the pseudoscientific energy present in all things and beneficial to humans. Unique stones, pyramids, and other new-age methods focused orgone energy, improving physical and mental health. Reich’s most famous book on the subject is The Function of the Orgasm. You can imagine which activity Wilhelm proposed enhanced orgone the best because he was, after all, psychoanalytically trained, and libido ranks high for psychoanalysts.

“Shut the fuck up,” I sneered, so he explained that Reich devised breathing and movement techniques for helping clients to pinpoint concerns. Typically, clients lie on their backs with their knees bent up and hands at their sides. With the therapist’s guidance, they identify muscular tension areas and then use breathing to release it. Anger, frustration, and many feelings are released by exhaling them out of the body. That aspect influenced Mark’s dissertation, not orgone. So, okay.

Mark employed these methods at the end of training weekends to help volunteers deflate after a long weekend of deep, emotional toil. If there was any orgone enhancement happening, I wasn’t invited. Where do I file my complaint?