Soap Opera

Twin Peaks is a murder mystery and a soap opera. Lynch and his creative partner Mark Frost intend no soap-opera parody here, as some have hypothesized. No, he’s giving us a soap opera wrapped around a murder mystery. During the summer of 1980, Americans wondered who shot J.R. Ewing, the villainous Texas oil man from Dallas. From magazines, newspapers, and casual barbecue conversations, speculation was everywhere. Everyone posited theories. Ten years later, people wondered with equal excitement, “Who killed Laura Palmer,” absorbing episodes and trading opinions around water coolers everywhere. Along the way, they learned all about the peccadillos saturating Twin Peaks, no different from Pine Valley, Llanview, or Port Charles for the sordid business the inhabitants pursue, only stranger. Of course, soap operas are by definition self-owning and over-the-top dramatic.

Magical Realism

Twin Peaks borrows much from magical realism, where magical elements occur within a real-world setting and become ordinary. Discovering that an extra-dimensional Black Lodge exists, that the FBI has a blue-rose division dedicated to investigating paranormal cases, and that doppelgangers and tulpas walk among us may shock characters, but only as much as learning your new husband wears a toupee might shock you, not in the same way as learning about ghosts or vampires existing would. Twin Peaks isn’t urban fantasy, though. With urban fantasy, the magic is considered strange to the setting, and with magical realism, it’s a normal part of everyday life. Time travel, for instance, is just another Tuesday in Twin Peaks, Washington.

Discussing his novel The Secret History of Twin Peaks with Ryan W. Bradley of Electric Literature, Mark Frost shares how magical realism applies for his book and possibly the Twin Peaks phenomenon overall:

If you can drop something into a person’s life that cuts a hole in that veil for a minute . . . It always seemed to me, from a shamanistic standpoint, to go back to Joseph Campbell, that’s what art is supposed to do. That’s what storytelling is supposed to do. That was its function in a tribal society. It was supposed to cathartically get you out of yourself and give you a point of view on yourself that maybe you didn’t have before. So, I was hoping to do something here that would be a sort of American magical realism.

Isabel Allende and Gabriel José García Márquez are masters of magical realism, and so are David Lynch and Mark Frost. Writing for Comic Book Resources, Robert Vaux tells us more about Lynch’s intentions:

Lynch finds the [soap opera] genre fascinating and often looks at ways it can be subverted or blended. It gives his films a sheen of magical realism, where events follow their own strange logic, and nothing is quite what it seems. Innocence and corruption play large roles in his work, often taking on larger-than-life qualities in the process. Blue Velvet, for instance, pulls back the cartoonish pure façade of a small town to reveal a cabal of sociopathic fiends lurking in the shadows. In contrast, The Elephant Man reveals a profoundly human soul hidden behind a disquieting surface, revealing the evil in plain sight from a “respectable” society that treats him like an animal.

Lynch subverts and blends the soap opera genre through his magical realism lens, which is precise and cutting. He’s a cinematic Muhammad Ali deploying his rope-a-dope methodology. Again, he isn’t satirizing but amplifying established tropes while presenting them from fresh angles, including viewer angles. If you come to a fork in the road, take it, many postmodernists have quipped. Why depend on authors completely for direction and interpretation? Do your own work.

Women

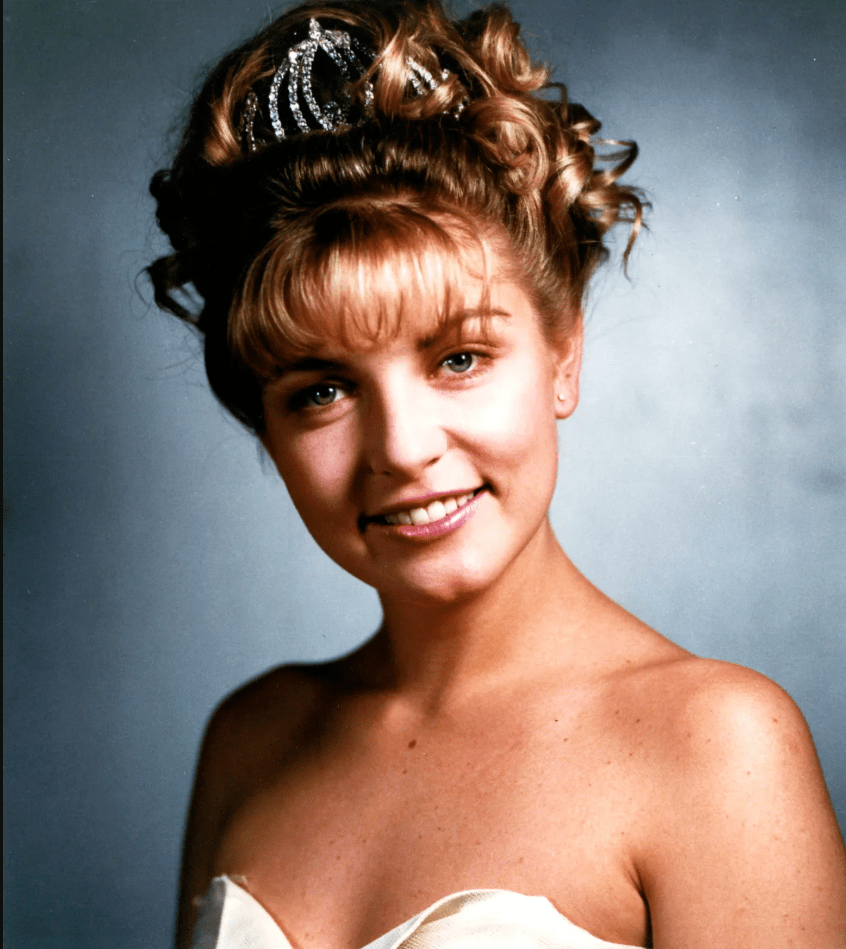

Twin Peaks: Fire Walk with Me reveals the underbelly of women’s existence and contains more emotional triggers than the three television seasons. Now that he’s moved beyond network limitations, Lynch shows no mercy, fully depicting Laura Palmer’s suffering and degradation and how men exploit her ruthlessly. Not since Promising Young Woman and The Handmaid’s Tale have I witnessed such brutality without having it descend into misogyny. So much for the happy façade beaming from that famous photo: Laura Palmer, the smiling homecoming queen, sporting an elaborate updo and royal tiara. Dreams for the future? Not likely. Lynch has covered this territory before, as Megan Burbank outlines in an article for The Stranger:

It’s also clear that their characters’ suffering isn’t being used simply to shock viewers. Lynch frames their stories in a way that humanizes the women at the center, which is what makes him so difficult to emulate; without this sense of care paired, it’s easy to make something exploitative or just bad.

I hear similar stories almost nightly while preventing suicide, countless women illustrating their lingering emotional wounds, and PTSD induced by cruel fathers, husbands, and boyfriends. Lynch begins building the effect with sequences involving One Eyed Jacks, a brothel just across the Canadian border staffed by underage sex workers. The initial “ick” becomes absolute horror during Fire Walk With Me. Lynch stops pulling punches, soundly displaying Laura Palmer’s plight, humanizing her, and shoving the patriarchy’s abuses into daylight.

Final Thoughts

If you’ve avoided Lynch because his style seems inaccessible, don’t worry. I’ve never been invited to occupy the front row of any classroom and encountered no trouble understanding the narrative, however nontraditional. Many details will inspire ongoing debate, but nothing’s too opaque for consumption. The content makes sense once viewers decipher how to approach it. My initial impressions are surface-level and nothing new to longtime fans. Twin Peaks pros have produced several volumes offering deeper understanding. Would I make a return visit? Absolutely. I’m sure the Great Northern has excellent rates for repeat customers.