I’ve told this introductory story before, and I’m retelling it now in a different context. You can see the original here. A seminal memory from my time in Ukraine involves a working vacation during my first summer there. Friends from my city, Ternopil, owned an enormous cabin outside Yaremche, a major skiing center in the Ivano-Frankivsk Oblast of Southwest Ukraine. For three weeks, I taught children verbs and articles, hiked through the Carpathian backwoods, and consumed shashlik, varenyky, and holubtsi — food, food, and more food! Finally, our last weekend arrived, and the mothers, who were my university colleagues, called me from the garden into the cabin’s living room. Together, they presented me with a hand-embroidered vyshyvanka, an intricate shirt embodying Ukrainian culture and history. I changed into the shirt. Then my friend Ruslana Stepanivna tied a matching sash around my waist. Next, my young female students appeared wearing traditional Ukrainian garb. Then, two sisters who lived nearby and had joined our lessons brought out their Sunday best. We went out to the patio for photos. Quite a scene, indeed.

Afterward, I quipped, “Will this go straight to the Kyiv Post’s advertising department? A big university promotion?” I’d played show pony more than once. Ruslana shook her head and said:

“Ні, Чак, ти не розумієш. Тепер ти українець.” (No, Chuck, you don’t understand. Now you are Ukrainian.)

The gift signified my acceptance into their community. I was no longer a foreign Peace Corps volunteer and had become, in their eyes, one of them. Ukrainian legend says that male outsiders can advance to Ukrainian status by completing three tasks: (1) they must climb Hoverla, the highest peak in Ukraine; (2) they must drink horilka (vodka) with a “professional,” a person widely regarded for drinking prowess; and (3) they must marry Ukrainian women. I only achieved two, but that didn’t matter. To them, I was in, and they couldn’t have symbolized acceptance any more than with a formal shirt embroidered with cultural history. I’m not sure if foreign women were tasked similarly or if they were tasked at all. I do note that many received embroidered blouses, and I’m sure they were much more worthy than I.

The word “vyshyvanka” derives from the verb вишива́ти (vyshyvaty, to embroider). The suffix -анка denotes that any clothing embroidered is a vyshyvanka, although most commonly it’s either a shirt or blouse. I once met a young man sporting a white suit embroidered with patterns native to his region. He explained his grandmother had done the handiwork. I couldn’t have imagined the hours she spent, needle between fingers, imbuing that cloth with her loving magic. Props to her and all women practicing this important skill.

In Echoes of the Past: Ukrainian Poetic Cinema and the Experiential Ethnographic Mode, J.J. Gurga explains how vyshyvanka functions figuratively:

The vyshyvanka is used as a talisman to protect the person wearing it and to tell a story. The person who created and manufactured it is also protected by evil intentions. A geometric pattern woven in the past by adding red or black threads into the light thread was later imitated by embroidery and believed to have the power to protect a person from all harm. There is a saying in Ukrainian, “Народився у вишиванці,” which is translated as somebody was born wearing a vyshyvanka, so that is guarded, shielded, and defended by whoever made it. The geometrical figures represented in the Vyshyvanka originate from a single letter, word, or story; intentions while embroidering a Vyshyvanka are also very important because it is used to emphasize someone’s luck and ability to survive in any situation.

These “luck and survival” emphases resonate more deeply now that Ukraine is at war.

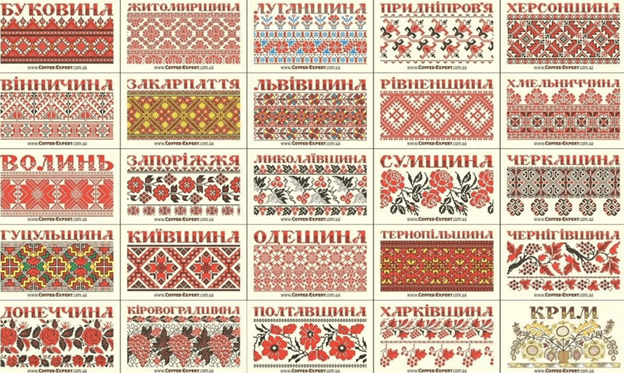

Ukrainians can tell someone’s home region by the vyshyvanka they’re wearing. Different colors, patterns, and designs relate tales and traditions sacred to different regions or oblasts. The vyshyvanka I own, for example, represents the Hutsul region of southwest Ukraine, and relies heavily on geometric patterns and cross-stitching. Alternatively, designs from central or eastern Ukraine might be white-on-white, red-blue, or red-black. Some regions focus on plant imagery, and colors vary.

The history of this wearable art form runs deep. In 513 BCE, Herodotus spoke about how the Thracian and Dacian people, inhabiting what is now the Balkans and Western Ukraine, decorated their clothing with embroidery. Anna Vsevolodovna, sister of Volodymyr Monomakh, Grand Prince of Kyivan Rus from 1113 to 1125, established a school for girls dedicated to embroidery, embedding its importance in Ukrainian culture. More contemporarily, designers such as Jean-Paul Gaultier have incorporated vyshyvanka themes into their creations. Ukrainians would not consider this appreciation, not appropriation. In fact, vyshyvanka designs have come into vogue as individuals wear them to support the Ukrainian nation and culture, currently threatened by Russian invaders. A FAQ and answer on the Ukrainian national board reads:

Can I wear a vyshyvanka without it being cultural appropriation? The straightforward answer is, unless you’re Russian, wearing a vyshyvanka is completely acceptable. In fact, Ukrainians deeply appreciate seeing foreigners donning vyshyvankas as a gesture of respect and solidarity, especially during these challenging times.”

The second time I wore my vyshyvanka was at a Eurovision party hosted by friends in 2016. Two years earlier, Russia had taken Crimea from Ukraine, and tensions were rising into what would become an invasion in 2022. My vyshyvanka was not cosplay. I wore it in support of a nation under attack from a hostile entity. I wore it to support my colleagues, now my Ukrainian family. Finally, of course, I wore it in support of Jamala, the Ukrainian entry that year, a Tatar whose outfit featured fine lace patterns of symbols important to Crimean Tatars that blended with the overall color of her suit. She won! Слава Україні (Glory to Ukraine!) The next time I don my Ukrainian garb will be when, not if, Putin is driven permanently from Ukraine, and once again I will shout, Слава Україні!